Getting yourself ready — May 6-12, 2019

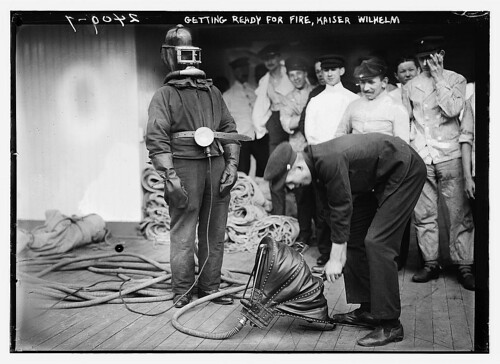

"'Getting Ready for the Fire, Kasier Wilhelm' Bain Collection, Library of Congress hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ggbain.10412 Call Number: LC-B2- 2400-7"

Welcome! This workbook is made by converting several plain-text files into a fully-operational website using the MkDocs static website generator. That means, you can keep a copy of all these files for your own records. Simply click on the 'Edit on GitHub' link at the top right. This will bring you to the repository that houses this workbook. Then, when you're signed into GitHub, you can fork (that is, make a copy) the repository into your own account.

Why 'forking'? It seems an odd phrase. Think of it like this: Writing, crafting, coding: these are like a small river, flowing in one direction into the future. You get new ideas, new hunches: the river branches. There's a fork in its path. Sometimes new ideas, new hunches, fold back into that original stream: they merge.

GitHub is a way of mapping that stream, and a guide to revisiting the interesting parts of it.

It's not the best metaphor, but it'll do. No doubt you've had that experience where, after working on an essay for days, you make a change that you regret. You wish you could go back to fix it, but ctrl+z only goes so far. You realize that everything you've done for the last week needs to be thrown out, and you start over.

Well, with 'versioning control', you can travel back upriver, back to where things were good. There are two tools that we will use to make this happen: git and GitHub. You'll learn more about making those things work in Module 1. You'll see why you'd want to do that, and how to future-proof your work, writing things in a plain-text format called 'Markdown'.

In Module 2, we'll start exploring the wide variety of historical data out there. We'll talk about some of the ethical dilemmas posed by having so much data out there. Data are not neutral 'things given'; rather, they are capta: things taken.

NB I am assuming, in this course, that the digital materials we want have already been digitized. Digitizing, adding meta-data (information that describes the data), and structuring it properly are very complex topics on their own that could be the subject of a complete course! If you are interested in those problems, a good place to start is this open course from the University of London's School of Advanced Study on database design for historians.

In Module 3, we'll see that data/capta are messy, and that they make a kind of illusory order that as historians, we are not normally in the habit of thinking about. The big secret of digital history is that the majority of your time on any digital history project won't be finding the capta, won't be analyzing the capta, won't be thinking about the historical meaning of the capta. We'll be cleaning it up. The exercises in this module will help you do that more efficiently (and be aware that 'efficiency' in computing terms is not a theoretically neutral idea!).

In Module 4, we talk about doing the analysis. I present finding, cleaning, and analyzing as if they were sequential steps, but in reality they are circular. Movement in one aspect often requires revisiting another one! This module explores how we do this, and what it means for us as historians.

In Module 5, we begin at last to think about how we communicate all of this to our audiences. Look at how one university lays out the expectations for digital history work (and, do you see how this ties back to ideas about paradata?). We will think about things like typography and layout. We'll look at ways of making our visualizations more compelling, more effective. We will also learn how to create an online digital exhibit using Omeka.

Finally, while there is no formal requirement for you to do this, it would be a great way of launching yourself as a digital historian to think about how you would formally reveal your project work in this class to the wider world: and then do it. There's a lot of noise on the internet, especially when it comes to history. How do you, as a digital historian, make the strongest possible signal?

What you need to do this week

- Follow the instructions below to set up your digital history workspace.

- Annotate the course manual for any parts of it that are unclear (or alternatively, that have you excited).

- Respond to the readings and the reading questions by annotating the readings themselves - see the instructions below.

- Submit your work to the course submission form.

Setting up a your workspace

A digital historian needs to have a digital workshop/lab/studio/performance space. Such a space serves a number of functions:

- A scratch pad / fail log and code repository so that we remember what we were doing, or (more importantly) what we we did - that is to say, the actual commands we typed, the sequence of manipulations or data moves.

- A narrative that connects the dots, that explains the why of that what and how. You can use this narrative to point to when sharing your work with others. Digital history is not done in isolation or in a vaccuum. Sometimes, you will need to share a link to your work (often on twitter) asking, 'does anybody know why this isn't working?' or, 'does anybody know a better way of accomplishing this?', or, 'hey, I'm the first to do this!'

- A way of keeping notes on things we've read/come across on the web. There are a number of ways of accomplishing this. In this course, I will mandate one particular solution: Hypothes.is.

- When you're working with academic databases such as JSTOR, then you'll also need a bibliography manager. We don't go into this aspect very much in this course (if you take other courses with me, you will) but you might want to check out Zotero.

- It can sometimes be useful to make little videos of your work to explain when something isn't working - Screen-cast-o-matic is free and does a good job.

Hypothes.is

Hypothes.is is an overlay on the web that allows you to highlight or annotate any text you come across (including inside PDFs). All of your annotations can then be collected together. It is a very effective research tool.

- Create an account with Hypothes.is.

- Get the Hypothes.is plugin for Google Chrome. If you don't have/use Google Chrome, go to the Hypothes.is start page and click on the 'Other browsers' link.

Once you're logged into Hypothes.is, and you have the plugin installed, highlight THIS TEXT and leave an annotation! Who will be first? There are a few different kinds of annotations you can make, noted in this list with videos showing them.

If you need step-by-step instructions for installing and using Hypothes.is, please visit the Hypothes.is help page and/or watch the video below:

Annotations are public by default. When you are making a new annotation you can toggle the visibility so that they are private and thus visible only to you.

You can also 'tag' any annotation you make. If many people use the same set of tags, you can collect annotations by tag. This can make it easier to do group research projects, for instance.

Important information about annotating

Please join our private HIST3814o annotation group. Remember to make all annotations to that group! Earlier iterations of this course used the ‘public’ group, and you can still see their annotations. However, we realized that it wasn’t fair to the people whose work we were annotating to have year after year of our annotations littering their page. Remember then: make your annotations in our HIST3814o group!

GitHub

Finally, you need a GitHub account. We will go into more detail about how to use GitHub in the next module. For now, go to GitHub.com and sign up for a new account. Follow all the prompts, and make a note of the direct URL to your account (mine for instance is http://github.com/shawngraham). You'll learn how to use this space in Module 1, Exercise 3.

Fail Log

Each week you will upload a fail log to you GitHub account. You will include a link to your 3 most important Hypothes.is annotations and reflect on how those 3 annotations were meaningful to your learning. In the first week you will also reflect on your worries for the course, any technical issues you encountered, etc.

This week, you will fork the fail log example ('fork' is a GitHub term meaning to make a personal copy of a repository). To begin, follow the instructions below:

- Open GitHub.

- Login to your GitHub account.

- Navigate to the example fail log repository on GitHub.

- Follow the instructions for getting started with the example fail log.

Your digital history lab/studio/workshop

You now have a digital history lab equipped with all of the necessary ingredients for doing digital history. You have an open notebook for recording what you are up to (both your narrative and your annotations). In GitHub, you have a scratch pad \ fail logfor keeping track of the actual nuts-and-bolts of any digital work you do (and note that it is entirely possible to do digital history successfully without having to do anything that a Computer Scientist for instance would call coding). You have a domain that you control completely, and where you can install other platforms and services as seems necessary.

VPN & DH Box

To access our virtual computer, the DH Box, you will need to use Carleton's VPN service. Please visit Carleton's VPN help page and follow the instructions for your particular computer. Once you've got it installed, you will need to connect to Carleton through the VPN with your MyCarletonOne credentials. Indeed, you should always connect via a VPN whenever you're using a public wifi point (like in coffee shops). The VPN acts like a private tunnel from your computer to Carleton's servers. To the rest of the internet, it will now look as if you actually are on campus. Once you're connected via the VPN, you can access the DH Box through your browser. Bookmark the site; you'll use it in the exercises in Module 1.

Using the DH Box

- Click the 'Sign up' button

- Fill in the form. Choose a username and password that you'll remember. You don't have to use a real email by the way, just something that looks email-like (this is handy if, like me, you end up creating multiple DH Boxes - it's a bad idea to have more than one DH Box with the same email address)

- Select the most time available (which will either be 1 or 2 months).

- Your personal DH Box will be created. Your username will now appear in the top right side of the purple bar. To enter the DH Box, click the username, select 'Apps'.

- A new tool ribbon appears below the purple bar. Most of what you will do in this course involves the 'Command line', 'RStudio', and 'File Manager'.

- Anytime the Command line or RStudio should ask for your username or password, you use the DH Box username and password you just created.

A note on using the university computer labs: If you are using an official University computer lab computer to access DH Box, aspects of the University's security system might block the RStudio aspect. I am working on a solution to this problem. If you know that you are going to have to use Carleton computers, get in touch right away.

Some Readings To Kick Things Off

What is digital history anyway? How is it connected to so-called 'big data'? Read the following pieces. Annotate with Hypothes.is anything that strikes you as interesting using our HIST3814o group; annotate anything that puzzles you - feel free to just say, 'I'm not sure what this means; does it mean.... does anybody have any ideas?' and if you see someone is asking questions, you can reply to that annotation with thoughts of your own!

NB Each week, I expect you to respond to at least someone else's annotation in a substantive way. No "I agree!" or "right on!" or that sort of thing. Make a meaningful contribution.

Once you have read and annotated the works, update your fail log in your GitHub repository . Explain why you're in this class, your level of comfort with digital tech, the kinds of history you're interested in, and what you hope to get out of this course. Your post should link to relevant annotations made by you or by your peers. (Every Hypothes.is annotation has a direct link visible when you click on the 'share' icon for an existing annotation).

Readings

Excerpts from Chapter 1, the Historian's Macroscope original draft; read from 'Joys of Big Data' to 'Chapter One Conclusion'. Use Hypothes.is to annotate rather than the 'commenting' function on the site, but remember to annotate using our HIST3814o group.

Jo Guldi and David Armitage, 'The History Manifesto: Chapter 4'

Tim Hitchcock 'Big Data for Dead People' https://historyonics.blogspot.ca/2013/12/big-data-for-dead-people-digital.html

'On Diversity in Digital History', The Macroscope. Read and follow through the footnotes to at least two more articles.

Acknowledgements

The writing of this workbook took place alongside the writing of my more formal book on digital methods co-authored with the exceptional Ian Milligan and Scott Weingart. I learned far more about doing digital history from them than they ever from me, and someday, I hope to repay the debt. Other folks who've been instrumental in getting this workbook and course off the ground include Melodee Beals, John Bonnett, Chad Gaffield, Tamara Vaughan, the staff of the EDC at Carleton University, eCampusOntario and of course, the digital history community on Twitter. My thanks to you all.

This class was first offered in the Winter 2015 semester at Carleton University in Ottawa Canada as HIST3907b. I am grateful to the participants in that class for the feedback and frank discussions of what worked and what didn't. To see the earlier version of the course, please feel free to browse its GitHub repository